JWST Detects Complex Organics 12 Billion Light-Years Away

by Jaymie Johns

December 6, 2025

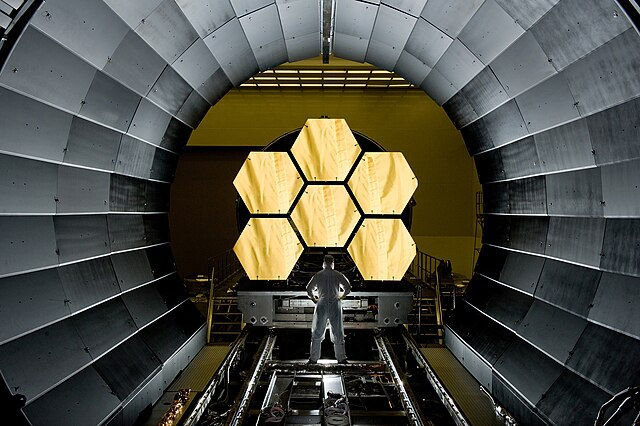

In a groundbreaking discovery that pushes the boundaries of cosmic chemistry, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected complex organic molecules in a galaxy more than 12 billion light-years from Earth. This distant galaxy, known as SPT0418-47, appears as it existed when the universe was just 1.5 billion years old—less than 10% of its current age. The findings reveal that the building blocks of life, in the form of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), were already widespread in the early universe.

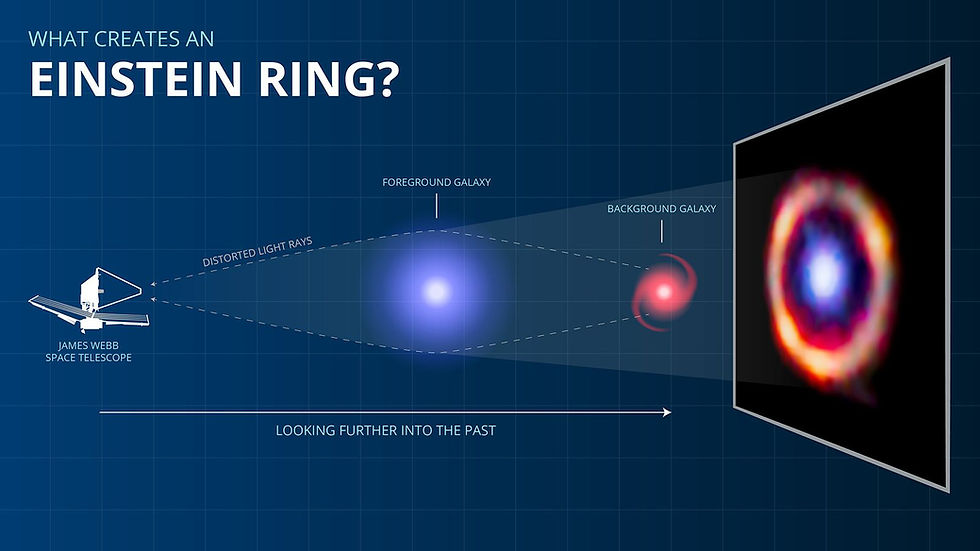

A Cosmic Magnifying Glass Reveals Hidden Chemistry

Detecting such faint signals from the dawn of time required extraordinary tools and a stroke of cosmic luck. SPT0418-47 is heavily obscured by dust, making it nearly invisible to previous telescopes. However, a foreground galaxy, located about 3 billion light-years away, acts as a gravitational lens—bending and magnifying the light from SPT0418-47 by a factor of 30 to 35, as predicted by Einstein's general relativity. This creates a striking "Einstein ring" effect, amplifying the distant galaxy's light enough for JWST to scrutinize it in detail.

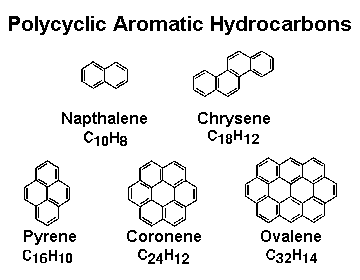

Using JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), astronomers identified strong spectral signatures of PAHs—large carbon-based molecules consisting of fused ring structures. On Earth, PAHs are found in soot, smoke, and smog, but in space, they are ubiquitous tracers of interstellar dust and star formation processes.

These molecules absorb ultraviolet light from young stars and re-emit it in the infrared, producing distinctive emission features—most notably at 3.3 microns—that JWST is uniquely equipped to detect. Prior telescopes lacked the sensitivity and wavelength coverage to spot them at such vast distances.

Rapid Chemical Evolution in the Young Universe

The discovery, published in Nature in 2023 by an international team including researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Texas A&M University, marks the farthest detection of complex organic molecules to date. "Detecting these complex organic molecules at such a vast distance is game-changing," said co-author Joaquin Vieira. The galaxy's interstellar gas is already enriched with heavy elements, indicating multiple generations of stars had lived and died, seeding the cosmos with the raw materials for advanced chemistry.

Surprisingly, the distribution of PAHs doesn't perfectly align with regions of active star formation—some areas show "smoke without fire," challenging previous assumptions. This suggests the early universe's chemical processes were more nuanced than expected.

Implications for the Origins of Life

PAHs are not life itself, but they are considered fundamental precursors to prebiotic chemistry—the kind that could lead to amino acids, sugars, and eventually biological molecules. Finding them so abundantly and so early implies that the chemical ingredients for life were distributed across the cosmos far sooner than previously thought.

As Justin Spilker, lead author from Texas A&M, noted: "It's remarkable that the universe can make really large, complex molecules very quickly after the Big Bang." If such organics were commonplace just 1.5 billion years after the universe's birth, habitable environments may have emerged much earlier and more widely than we imagined.

JWST continues to revolutionize our view of the early universe, hinting that life's building blocks are not rare cosmic accidents but a universal feature of galaxy evolution. Future observations promise to push even further back in time, potentially uncovering galaxies where these molecules are just beginning to form—or where they haven't yet appeared at all. For now, the message from 12 billion light-years away is clear: the seeds of complexity are sown everywhere in the cosmos.